What I Did

Reposted from Thus Have I Seen by Zhaxi Zhuoma Rinpoche p.220-231

In October 2019 a Chinese documentary was made about Buddhism in general and the role of H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III and His teachings in society, and the impact they are having and will continue to have on society. The China International Education TV from Beijing interviewed me and other senior students of the Buddha Master at our temples. They filmed the Holy Vajrasana Temple and the Holy Vajra Poles. Senior students and the abbots of other temples were asked other questions, but I was asked, “For Buddhism as a universal religion, besides promoting and inheriting the traditions, in which areas can we explore to adapt it to the modern world, to satisfy the religious needs of the mundane world, and to connect it with the values of the civil society, so that the development of Buddhism can sustain itself forever?” We were given several options on questions to answer and I picked this one. It was a subject that I had thought most about. It was one of the factors that prompted me to write this book. How can the correct teachings of Buddhism become an integrated part of our modern world and be sustained in that world? I had been drawn to the Buddha Master because I felt in my heart—long before I even suspected that He was a Buddha—that His teachings of Buddhism were like what I imagined the original teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha were like when He walked on this earth. That was what I had been looking for. Only, the Buddha Master was presenting them in ways that were adapted to the modern world in which we lived. My passion, my wish was to be able to help bring what He so marvelously taught us to the English-speaking world.

Given that, my answer to the question posed by The China International Education TV was, “H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III has told us that we must work to uphold the laws and aspirations of our nations and live together in harmony with others. The other unique and powerful influence of Buddhism is that it is inclusive of all, thus enabling it to have influence over other religions and belief systems. It does not promote dogma or teach that other belief systems are intrinsically evil. It does not require loyalty to any worldly leader. We have no pope or worldly hierarchy. One can remain Christian or Jewish or Daoist or what have you and still practice the Buddhist path and become an enlightened or holy being—a Bodhisattva.

“I remember H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III advising me before I spoke to a group of young Catholic men that not all Bodhisattvas are Buddhist. That is how Buddhism spread to other countries, it absorbed much of the local customs, including the local deities, while teaching the methods of enlightenment taught by Shakyamuni Buddha. H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III has given those of us living in the modern world the Supreme and Unsurpassable Mahamudra of Liberation that is available at many levels to enable us to become enlightened and be free of all suffering. One does not need to become a Buddhist to learn and practice this Dharma.

“We are building a Buddhist village around Holy Heavenly Lake in Hesperia, California that will serve as a model and center for Buddhist and non-Buddhist alike to come and learn and practice the Dharma; enjoy Buddhist art and architecture; and experience the spirit of Buddhism from a variety of different cultures. I plan on building a small temple and center there to help serve local English and Spanish speaking followers using indigenous adobe structures and “hermit caves” for those wishing to do long-term intensive retreats. I am also hoping to introduce some local Native Bodhisattvas to help make the teachings of the Buddha more ‘real’ for local people.”

They only used the first paragraph of my answer in the documentary, but I thought the rest of the answer captures my intent for the work I am doing or want to do in this world, and how I want to apply what I have both “seen” and “heard” from my Buddha Master. It sparked something in me that caused me to have hope again—to face my demons and stop being so chicken-like, and to reevaluate what I was doing. What was working and what was not? Why was this so? What could I do?

In order to realize that dream of reaching out to make the Dharma more real for local people, I had started several initiatives in addition to what I had been doing at the Holy Vajrasana Temple in Sanger to bring the true Dharma brought to this world by my beloved Buddha Master and that reestablished the original teachings held by Shakyamuni Buddha for our modern times. I would add this book as another initiative as well. I was particularly interested in sharing the teaching of the Buddha with non-Buddhists. Although you do not need to become a Buddhist to benefit from the teachings of the Buddha, if you continue to study Buddhism, I do believe your relationship to your original beliefs will evolve.

The initiative that I felt was most personally rewarding was work I had started with the prison community of women at the Central California Women’s Facility at Chowchilla, California. I had dropped it when I was not able to go there because of my health and other restraints. The second initiative was the community of Spanish-speaking Buddhists, started in Northern California, but also on hold. The third was the start-up Dharma center in the Mojave Desert at the Holy Heavenly Lake site of the future Ancient Buddha Temple and Buddhist Village that we started in January 2020. These all had potential, but then the pandemic hit, and everything came to a stop. Let’s see what the pandemic did, but first let us look at each of these communities.

I still had faith in the Buddha and the Dharma, but in myself—not so much. Long before the virus, I had scheduled the month of June 2020 to be free of all events—no retreats, no trips, nothing. I would devote myself to the Dharma and beseech the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to help. They always did when I asked, but I had been too depressed or maybe embarrassed to ask. I knew that was wrong, but I lacked the will to change. It did not work out that way. I did not go on retreat. Instead, I wrote this book and devoted my time to the work of establishing and supporting an International Lemonade Sangha. I will explain how that happened, but first, let me tell what happened to the other three initiatives.

2018—Chowchilla Sangha

Part of the vow I took after conducting the Kuan Yin Bodhisattva’s Great Compassion Dharma Assemblies that were discussed earlier, was the vow to contribute any offerings made during those assemblies to freeing captive living beings. In most cases this involved releasing captive wild animals, insects, birds, or marine life, but I wanted to do something for captive human beings who were held in our local prisons, too. Normally this action must be done within a few days after the event, but I got a dispensation because of the red tape involved in doing anything in the California state prison system. I could send them Buddhist books and buy Dharma instruments for their chapels (after extensive and time-consuming vetting), but what else could I do? Most of our books were still in Chinese.

I developed a strong desire to do prison work after returning from the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in September 2016. I had traveled there with Gesang Suolang Rinpoche and met Bhikshunni Pannavati and other Buddhists to join the Dakota Access Pipeline protests and to see first-hand what was happening, to show support for their cause, and to join the Oceti Sakowin59 camp (FIGURE 86). Gesang and I had also gone on to the small Mandan, North Dakota, jail for a separate protest concerning a native woman who was incarcerated there. All of this caused me to remember a vivid vision I had had many years ago where I was told I should help those in prisons. I was also told to construct a tipi and paint it with certain symbols, which I did, but that is another story. I had tried to do work with prisoners when working with the Kickapoo Nation while I was in Kansas and often asked for guidance of tribal leaders on what I could do. Finally, a wise Pottawatomie Medicine Man told me, “Know that not all prisons have walls.” With that I proceeded along other paths, but that mandate was always there to work with those who did have physical walls confining them. When I came back to the temple from the Standing Rock reservation, I was determined to do something to bring the correct Dharma to inmates. After I explained what I wanted to do to my Buddha Master, He was delighted and encouraged me to do so.

FIGURE 86: Standing Rock Encampment—our camp was under the tree with the maroon and saffron Eternal Knot Tibetan door hanging from the tree.

I started by contacting a Buddhist Chaplain group I had trained with earlier in the San Francisco Bay Area. I remembered that some of the group were working in prisons. I had not been able to join the class field trip to San Quentin60, but I serendipitously received an invitation to a seminar on prison chaplain work being sponsored by the group, I believe the same weekend after I arrived home from Standing Rock. I signed up and went to the Bay Area for the seminar and a reunion of my fellow students. I was able to find out from the other students where the closest prison to our temple might be. It turned out that perhaps the largest female prison in the world was less than 45 minutes away from the temple, north of Fresno, near Chowchilla. There had been two women’s correctional institutions there, but as they reduced the population of female prisoners, one had been converted to male use. I stopped to check them out on my way home from the Bay Area Chaplain seminar. That only gave me a glimpse of their bleak exterior and the name of the person to contact about visiting the facilities. I contacted the most delightful rabbi who was not only in charge of the Jewish prisoners, but also had those who were or considered themselves to be Buddhists. As it turned out, he was interested in doing more to seek out those of Buddhist persuasion or interested in Buddhist practice and was very eager to have some help. The California State system does not have any Buddhist Chaplains, even though they have every other conceivable group represented. In recent years there had been a lot of emphasis on religious freedom and meeting the inmates’ spiritual needs. So, after personal TB tests and much red tape, I was given permission to enter the prison and meet with the twenty to thirty women there who were interested in Buddhism.

I tried to meet at least once a month with this group of inmates. Seven women took refuge. Since the women hold jobs at the prison and cannot always arrange their schedules to attend our classes and services and are both released and transferred to other facilities, it was often a different group that attended each session. It was challenging, but very rewarding. The women are amazing, eager to learn the Dharma, and very insightful. Not all of the group I met with are “releasable” but are “lifers” —some with no hope of parole. They understand impermanence and karma—in spades. It is something they face head-on every day. I do not think that is true for all of the women in the prison, but for the ones who find their way to Buddhism, it is true. One of the most serious students is like this. She is not only working on herself; she works to bring others to the Dharma as well. I am very impressed with these women and their spiritual capacity and affinity with the Dharma.

Guard towers located around the octagon-shaped site are occupied by armed guards keeping a watchful eye on the inmates. I was not allowed to wear maroon or any other colors worn by the inmates–they even confiscated a chartreuse handkerchief I once had with me. They are very careful about anything that can be used for gang communication. And, yes, the women have gangs that control their behavior both inside and outside the prison walls. I also found they have alcohol (known as pruno, hooch, or toilet wine)—being very resourceful in what they use to ferment what I understand is a deadly brew. I found this out because one prospect told me she could not take refuge when she found out what our five precepts entail. I had not anticipated that.

The chapel is a sort of oasis where the women can go to participate in spiritual programs of just about anything you can imagine. I witnessed a very touching scene where one of the inmates came to see the chapel staff to give a teary-eyed goodbye after she just found she had been released. It seemed she didn’t really want to go. It is scary on the outside, too. The chaplains and religious volunteers were special.

Things are very severe and whatever you are doing can be interrupted at any time by blaring loudspeakers announcing where you need to be or what you need to do. It is hard to find time to concentrate, but the women here seem to be able to do it. All the inmates are counted several times during the day. Once there was some sort of disturbance when I was leaving, and all the women had to instantly drop and remain on the ground until control was reinstated. With armed marksmen watching every move and having authorization to shoot. You do not deviate from protocols. They installed video cameras everywhere in the Chapel after I started going there, so we were constantly under surveillance as well. And the rules concerning what you can and cannot do are maddening—no hardbound books or notebook binders are permitted. It is amazing what can be weaponized. They warned us at orientation that the system does not negotiate to release hostages. Once I had my own “brown-card,” I could at least bring a suitcase in with my books and lunch, but before, I could not even carry a purse. Once, all of the chaplains were away from the chapel for a short time and I was given the alarm to carry on me. I am not sure what would have happened if I had pushed the alarm bell, but I was warned that I would not want to find out and I believe the person who warned me.

I finally did get a glimpse of what the rest of the prison, aside from the Chapel, was like and how some women lived when I was taken to the “Condemned Housing” where the inmates with death sentences and those considered more dangerous were housed. It was not what I expected. The good rabbi warned me that there was no way he could describe the experience and he was right. This is the only facility in the state having a death row for females. There were 23 or 24 women, of which five had indicated they are or want to be Buddhists. I believe all those on death row have been convicted of murdering at least one person. Some have been there for over 20 years. Several have exhausted all hope of parole or appeal. At present the State is not executing anyone, but that could change at any moment. California has not abolished the death penalty. I was only able to meet three of the Buddhist women there and spend time with two, but I still hope to return. There is no place to sit, and you have to put on an armored vest to enter, but they are so eager to learn Dharma that it is worth the effort. They do have access to some books and just discovered a correspondence course from I think the Amitabha Buddhist Society, a Pure Land Group. I am not allowed to offer any correspondence-like program since I have physical access to the prisoners. You cannot do both. I did donate as many books as I could along with certain Dharma instruments. I have acquired several supplies of malas (Buddhist rosaries) that some of the women wanted and could have if they met the strict prison standards. So far, I have not been able to give them malas. One set was too big, another had tiny metal beads, and so on. Everything is heavily vetted.

I had to stop visiting the prison because of restrictions on visitors and my failing health issues. I miss the classes and the inmates very much. I suspect I learned as much as anyone. I am not sure if I will ever be able to return and that saddens me. The chapel is a long walk deep within the prison and I am not at present physically able to make the trek. Perhaps when the Covid pandemic is over and it is safer to go out, I will be able to meet them at the prison again, but for now it may be best that I develop another means to communicate with them.

2019—Spanish Sangha and Bilingual Classes

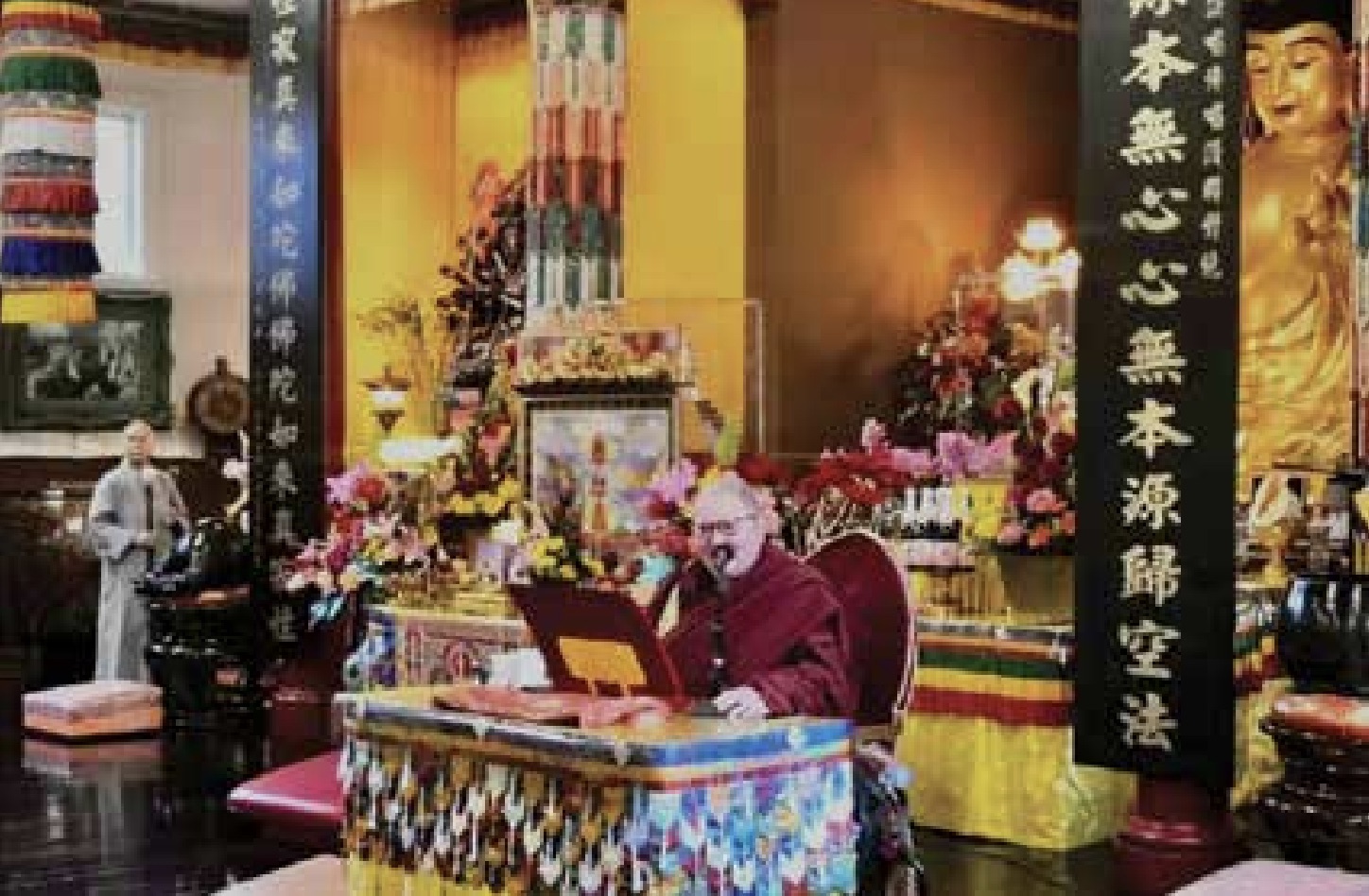

Last year, I met a young Hispanic man from Ecuador who wanted very much to learn more about the Dharma and was quite interested in the Buddha Master. He had studied and practiced Buddhism for years and it shows. I think he found me via our temple website. He has a young and quite spiritual wife from El Salvador and young children. She still has limited English skills, so he would try to translate any of the English readings that I gave. They lived near an Amtrak line in Stockton, California that also runs to Fresno as well as the Bay area. The train schedule was such that I could arrive and leave the same day and still have enough time for a class, enjoy lunch with them, and return before nighttime. I could handle that. Other Spanish students were able to join us from the bay area and several local non-Spanish speakers came as well. Another excellent translator joined the group and the two translators worked very well together to translate whatever I would read from the Buddha Master. They were wonderful classes. Those of us who did not understand Spanish also benefited from the process and the discussions (FIGURE 87). Our hosts had to relocate to San Jose to be closer to work and we started holding the Spanish Sangha classes at Hua Zang Si (FIGURE 88) until the novel corona virus of 2019 hit.

FIGURE 87: Reba Jinbo Rinpoche with Blanca and Edwin Miranda at their home in Stockton, California during a dharma class for the Spanish Sangha in Stockton, California.

FIGURE 88: Class for Spanish Sangha at Hua Zang Si in San Francisco, California. Zhengzhi Shi helped with the drum and bells.

Perhaps we will be able to start online classes with Spanish translation when we recover from the pandemic. We could reach more students that way, as there are Hispanic students in southern California who would benefit from these classes as well. Hesperia, where we now have a new Dharma center and hope to build another temple has a sizable Hispanic population, too.

2020—Xuanfa Holy Heavenly Lake Dharma Center at Hesperia

Remember in 2014 when I was told that I should move my long-term retreat center and start another temple for Western students in the desert in southern California? Well, that site is located in the small modest town of Hesperia in the Mojave Desert. Our site has 130 or so acres next to the usually dry Mojave River and contains a beautiful lake. It had been a sort of horse ranch and equestrian center with facilities for weddings and the like around the lake. I learned that the lake was a very special place, located on underground aquifers and the location of powerful crystals (FIGURE 89). It was a holy site and was going to become an even holier site as my Buddha Master was planning on building His residence there along with His Ancient Buddha Temple. It was to be developed as a Buddhist village with a series of canals connected to this magical lake. Different Buddhist groups would build their temples there. Others would develop shops and businesses related to the activities of the temple—a sort of Buddhist Vatican City. My plans are to start another temple or Dharma center for non-Chinese speakers and have facilities for long-term retreats.

FIGURE 89: Zhizang Shi (Sonya) at Heavenly Lake, Hesperia, California.

On the first Sunday in January, 2020, we held our first class in temporary quarters. We now have 27 members of our Meetup group and several continued attending the online classes after we could no longer go to Hesperia because of the quarantine. One regular drives from Scottsdale, another from Salt Lake City, and several more come from San Diego and the Los Angeles area. I am very enthusiastic about this group, too. True, we are sort of in the middle of nowhere in the Mojave Desert, but we are also where H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III will be moving and have his main temple, and I still hope to start another Holy Vajrasana Temple there with Long-term Meditation Caves (FIGURE 90). For now, I will continue meeting with them via the virtual Lemonade Sangha.

FIGURE 90: Model of Proposed Long-term Adobe Meditation Cave/Hermitage.

So, what is the Lemonade Sangha? In early Spring of 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak caused us to close the temple to visitors and retreatants and stopped any travel or holding of classes anywhere. I had wanted to do distant learning for some time. We had started the Xuanfa Five Vidyas University in 2012 and did reach a few students. My intent was to enable us to have a program that allowed for long-term retreats by students from China who needed student visas to be here that long. Of course, it would serve other purposes as well, but there were few Western students who were any way close to being able to do a three-year plus retreat and the Chinese students who were, needed student visas. I did hold a number of Seven-Dharma System Seminars on various topics that were also helpful. I wanted it to be part of the XFVU program, but that never really worked out. I finally stopped XFVU, at least until we could get approved English translations of the major texts by the Buddha Master and hopefully of several of His discourses. That may still happen and with the use of Zoom meetings we may be able to offer those programs again.

When the virus was just beginning to have an impact on us, the rabbi chaplain at the women’s prison called me, to see if I was ok. The Chowchilla Sangha was concerned about my well-being. That was a wake-up call. I was so ashamed. I should have been calling about them. I immediately wrote them a long letter advising them on what they could do during the lock down and promised to keep them up-to-date with what was happening with me and our temple by sending them edited Blog articles. I was too late. The rabbi’s email sent back an automated message that he was not able to be at the prison either. That initiative was on hold, but it fired me up to start the Lemonade Sangha.

I talked with several of my students and we all agreed our lives were not that different. In fact, this sheltered-in-place order was not all bad. It gave us more time to devote to our practice and an opportunity to reassess our lives and recharge and reflect on our Dharma and cultivation practice. So out of this lemon called Covid-19 or the Corona Virus, we made lemonade. I wanted to start this effort as an invitation-only event. We were warned about zoom-bombers who were crashing many Zoom projects. That might create bad karma for anyone tempted to profane the Dharma.

I started with a mailing list of over 160 selected from the people who had been frequently opening my blog. The first Zoom based class on “What Is Cultivation?” was quite successful. There were over 75 who registered from eight different countries for either the Sunday afternoon classes or the related open mike discussion groups held every Saturday morning during the first four-week period. Over 35 persons participated in at least half of the class sessions. We will continue these events as long as there is interest. I suspected that when we were no longer under house arrest, the attendance would diminish as people became “busy” again. That happened, but not so much. There was a core group that remained interested.

We also started virtual morning services Monday through Friday at 6:00 am and at 7:00 am on Sundays. I pledged to continue the Saturday morning discussion forums or open mike sessions and the Sunday afternoon classes. These hours enable students from both Europe and Asia as well as all of North America to participate.

This virtual temple may be our primary temple and it was certainly the fire I needed to both do what I needed to do with my practice and to sit down and write this book. I want to reaffirm that the Dharma does work—that the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and Dharma Protectors will support you, if you let them. You still have to be open to that help and have faith in yourself. You do need to be that phoenix and rise up again and again. I am reminded of a Christian saying that the only difference between a saint and a sinner is that the saint never gave up. That applies to becoming a holy person in the Buddhist sense as well. The Dharma is wonderful and powerful and the empowerments may help clean out hindrances and obstacles, but the key is what you do. This practice is driven by you and the fact that you do have a Buddha Nature that is the same as that of all who have become holy beings—as do all living beings. The Buddhas can show us the path. We have to follow it ourselves.

Footnotes

59 The proper name for the people commonly known as the Sioux is Oceti Sakowin, meaning Seven Council Fires. Each of the Seven Council Fires was made up of individual bands, which were based on kinship, location and dialect — Lakota, Dakota or Nakota. ↩

60 San Quentin, is a notorious maximum security state prison for men in Marin County, just north of San Francisco. It has California’s only death row for male inmates and the largest in the United States, holding 700 condemned men in 2015 with a capacity for 715. Chowchilla has the only death row for female prisoners, but they would be transported to San Quentin for execution should that happen, as San Quentin has the State’s only execution chamber. There has not been an execution there since 2006. San Quentin was also the site of a major scandal during the Covid-19 outbreak when infected prisoners from another prison were carelessly shipped there, infecting and killing many of the San Quentin prisoners. ↩